| This article is part of a series and has been written by the Master’s students in Global Politics and Society at the University of Milan. As attending students of “The Welfare States and Innovation” course, they explored the connection between Social Innovation and new forms of Welfare in contemporary societies. The article highlights the development of new synergistic partnerships among actors involved in multi-stakeholder networks and innovative multi-level governance models for social policies. |

Energy poverty refers to a situation where a household is unable to meet its domestic energy needs. Europe is currently witnessing a geographical “energy divide”, that is a spatial and social inequality in access to energy. Relevant cleavages concern all European countries and populations. The article focuses on energy poverty and on its eco-social nature.

What is energy poverty about?

Nowadays, human beings heavily depend on energy resources for services that are vital for well-being and for ensuring a minimum standard of living. Energy poverty refers to a situation where a household is unable to meet its domestic energy needs, meaning that they cannot access necessary energy services at an affordable cost (Bouzarovski et al. 2020). Both in research and policy documents, various definitions of energy poverty are employed. However, two general focuses can be identified: one on households that allocate a significant portion of their income towards energy expenses, the second one on households that have inadequate expenditure on energy (Feenstra & Clancy 2020).

Energy poverty has far-reaching implications across various policy domains, encompassing health and social care, education, economic growth, and carbon emissions reduction. Tackling energy poverty holds the potential to yield multiple advantages, such as reducing government expenditure on healthcare, fostering higher levels of educational achievement, enhancing comfort and well-being, driving economic development, improving work performance, and ultimately mitigating carbon emissions (NEA 2020).

Presently, the world is confronted with three major energy-related challenges: energy poverty, energy supply security, and the energy transition (Zhao et al. 2022) . In recent years, the Covid-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine have drawn renewed attention to the social risks associated with poverty and energy poverty within Europe. Furthermore, the increasing focus on the environmental crisis and the imperative for a transition to renewable and low-impact energy sources have emphasized the need to consider the economic consequences of decarbonization on the most vulnerable segments of society. A proper and effective management of all elements related to a just energy transition should therefore aim to minimize the effects on local communities and maximize long-term benefits, creating conditions for the enhancement of sustainable regional development (Vatalis et al. 2022).

Energy poverty in Europe

According to Eurostat, approximately 36 million people in the European Union, which accounts for 8% of the population, faced challenges in adequately heating their homes in 2020. Furthermore, around 6% of the EU population experienced difficulties in paying their utility bills, while nearly 13% lived in homes that had issues with leaks, dampness, or rot in 2019. In 2018, the most economically disadvantaged households in Europe spent 8.3% of their total expenditure on energy (EPRS 2022).

The causes of energy poverty in developed countries have traditionally been attributed mainly to low incomes, high energy prices and poor housing efficiency (Rademaekers 2016). However, recent years studies have encompassed a wider range of dimensions, framing energy poverty as “a systemic challenge connected to broader socio-technical and governance infrastructures” (Bouzarovski et al. 2021). Overall, the upward trend in domestic energy prices and expenses over the past decade has not been counterbalanced by corresponding increases in purchasing power or improvements in energy efficiency, resulting in persisting growing levels of energy poverty (Bouzarovski & Tirado Herrero 2017).

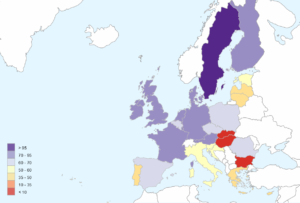

Bouzarovski and Tirado Herrero (2017) showed how Europe is currently witnessing a geographical “energy divide”, that is a spatial and social inequality in access to energy. According to the authors, in Europe this divide follows a traditional core-periphery division, with southern and eastern European countries as the most affected. The OpenExp European Domestic Energy Poverty Index (EDEPI) confirms these hypotheses (see Figure 1). The index is based on four indicators: 1) share of energy expenditures out of total expenditure; 2) share of the first income quintile population unable to keep homes warm in winter; 3) share of the first quintile population unable to keep homes cold in summer; 4) share of the first quintile population living in leaking homes.

Observing the EDEPI index, a gap in scores is evident between Western/Nordic European countries and Eastern/Southern/Baltic countries. According to the report, this difference is also linked to the impact of geographical location, as populations in Northern Europe predominantly face winter domestic energy poverty, while Southern Europe is potentially exposed to both summer and winter vulnerabilities.

This disparity is differentially experienced across social classes, as low income (usually linked to limited education and precarity) plays a significant role in driving energy poverty, but also along gender lines. The connection between energy poverty and the ability to pay energy bills should naturally bring attention to gender issues, given that in European Union there exists “a distinct gender income gap throughout all stages of life […] [and that] women are disproportionately found as heads of households” (Clancy et al. 2020). Indeed, household chores often entail substantial energy consumption. According to the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2021), a significant disparity exists in the performance of these tasks, with 93% of women regularly undertaking them compared to only 53% of men. This highlights an imbalance in terms of resilience against energy poverty, emotional labor of daily living, and addressing the inadequacy of energy services within the home (Petrova & Simcock 2021).

European measure to address energy poverty: an historical overview

Achieving a basic provision of energy goods and services involves addressing both economic affordability and ensuring material and infrastructural accessibility, in particular for vulnerable groups and regions. The European Union’s path in tackling energy poverty and energy efficiency began in 2009 and has intensified in recent years. Following a timeline of the European Union’s increasing attention towards the topic.

2009-12

Within the legislation of the European Union, the concept of energy poverty only emerged in 2009 within the Third Energy Package (2009/72-73/EC), which urged member states to “develop national action plans or other appropriate frameworks to address energy poverty” and to identify the most vulnerable households with the aim of supporting them through the social security systems and energy efficiency measures. Later directives encourage states to replace direct subsidies with measures aimed at reducing energy consumption, promoting renewable energy sources, and improving energy efficiency (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive 2010/31/EU; Directive on energy efficiency 2012/27/EU).

2016-18

The Commission put forward the ‘Clean Energy for all Europeans’ package in 2016 (approved in 2018) aimed at giving consumers secure, sustainable, competitive and affordable energy for every european. This package implements the Energy Union, covering energy efficiency, renewable energy, security of electricity supply and governance rules. In particular, it urged Member States to define a set of criteria for the purposes of measuring energy poverty.

2019

In December 2019, the European Commission present the European Green Deal, which aim at transforming the EU into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, ensuring through the “Just Transition Mechanism” that no person and no place should be left behind by providing targeted support to help mobilize resources in the most affected regions and to alleviate the socio-economic impact of the transition. The Just Transition Fund (2021-2027) supports the economic diversification and reconversion by involving investments in up- and reskilling of workers, as well as job-search assistance and support to small and medium-enterprises.

2020

The Renovation Wave strategy, published in 2020, focuses on three key areas: addressing energy poverty and improving the efficiency of underperforming buildings, renovating public buildings and social infrastructure, and decarbonizing heating and cooling systems. Regarding the former, the text of Commission Recommendation 2020/1563 explicitly states that “there is no standard definition of energy poverty, and it is therefore left to Member States to develop their own criteria according to their national context”. Therefore, Member States are encouraged to formulate national energy and climate plans (NECPs) to: assess the number of households experiencing energy poverty; implement measures to tackle energy poverty; ensure that households have the right to access electricity at reasonable, easily comparable, transparent, and non-discriminatory prices.

2022

Another key action is the RePower EU initiative launched in May 2022 in the context of the war in Ukraine. It aims at enhancing the resilience, security, and sustainability of the EU’s energy system through necessary reduction of dependency on fossil fuels and diversification of energy sources.

2023

The new Social Climate Fund will provide dedicated financial support to help vulnerable citizens and micro-enterprises to address energy poverty, both in the short and in the longer term, through different measures, including: reduction in energy taxes and fees or provision of other forms of direct income support to address rising of energy and fuel prices; incentives for building renovation and for switching to renewable energy sources.

Conclusions. The importance of an eco-social perspective

Energy poverty, with its detrimental effects on people’s health and well-being, constitutes a distinct manifestation of poverty. It poses a significant societal challenge and has the potential to greatly impact the climate resilience of those affected (Creutzfeldt 2020).

As shown, energy poverty encompasses both ecological issues, economic decisions and social problems. On one hand the inefficiency of low-income residential buildings leads to higher energy waste and higher pollutant emissions per unit of energy, and on the other provides for environmental gains but risks exacerbating pre-existing economic and social inequalities. A “triple injustice” risk to occur, where those who pollute less are the most exposed to risks and are also the least equipped to protect themselves (Mandelli 2022).

The European Union’s path towards a just transition highlights that these three dimensions cannot progress independently, and it is necessary to consider climate needs and economic challenges within the social framework. This eco-social approach is crucial to prevent the ecological transition from burdening the most vulnerable population groups and exacerbating social inequalities, and it will be increasingly necessary to formulate social policies in ways creating synergies with environmental goals (Koch 2018).

References

- Bouzarovski, S., & Tirado Herrero, S. (2017). The energy divide: Integrating energy transitions, regional inequalities and poverty trends in the European Union. European Urban and Regional Studies, 24(1), 69-86.

- Bouzarovski, S., Thomson, H., & Cornelis, M. (2021). Confronting energy poverty in Europe: A research and policy agenda. Energies, 14(4), 858.

- Bouzarovski, S., Thomson, H., Cornelis, M., Varo, A., & Guyet, R. (2020). Towards an inclusive energy transition in the European Union: Confronting energy poverty amidst a global crisis. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium.

- Clancy, J., Özerol, G., Mohlakoana, N., Feenstra, M., & Sol Cueva, L. (2020). Engendering the Energy Transition: Setting the Scene, 3-9. Springer International Publishing.

- Creutzfeldt, N., Gill, C., McPherson, R., & Cornelis, M. (2020). The social and local dimensions of governance of energy poverty: Adaptive responses to state remoteness. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43, 635-658.

- EIGE – European Institute for Gender Equality (2021). Gender Equality Index 2021: Health. Gender Equality Index Report.

- EPAH – Energy Poverty Advisory Hub (2022) Introduction to the Energy Poverty Advisory Hub (EPAH) Handbooks: A Guide to Understanding and Addressing Energy Poverty.

- EPRS – European Parliamentary Research Service (2022), Briefing: Energy poverty in the EU.

- Feenstra, M., & Clancy, J. (2020). A view from the North: Gender and energy poverty in the European Union. Engendering the energy transition, 163-187.

- Koch, M. (2018). Sustainable welfare, degrowth and eco-social policies in Europe. Social policy in the European Union: state of play, 35-50.

- Mandelli, M. (2022). Understanding eco-social policies: a proposed definition and typology. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 28(3), 333-348.

- NEA – National Energy Action (2020). The Multiple Impacts of Energy Poverty. EU Energy Poverty Observatory (EPOV).

- Petrova, S., & Simcock, N. (2021). Gender and energy: domestic inequities reconsidered. Social & Cultural Geography, 22(6), 849-867.

- Thomson, H., Bouzarovski, S., & Snell, C. (2017). Rethinking the measurement of energy poverty in Europe: A critical analysis of indicators and data. Indoor and Built Environment, 26(7), 879-901.

- Vatalis, K. I., Avlogiaris, G., & Tsalis, T. Α. (2022). Just transition pathways of energy decarbonization under the global environmental changes. Journal of Environmental Management, 309, 114713.

- Zhao, J., Dong, K., Dong, X., & Shahbaz, M. (2022). How renewable energy alleviate energy poverty? A global analysis. Renewable Energy, 186, 299-311.